Sixty years of service

“He’s very much a people person. He’s very caring. A great man of faith and a true gentleman.”

We’d bumped into Barbara at the café at Truro Cathedral. She was a former parishioner of Canon Michael’s, from Padstow.

She was one of several people we happened to meet who knew him. Everyone had only good things to say about him.

“He’s a wonderful priest, a wonderful friend, a very godly man and a pleasure to know,” said Canon Jane Kneebone.

“And he’s a very humble man,” added his wife Jan.

The Reverend Canon Michael Fisher is celebrating sixty years of ordained ministry in the Anglican Church. It seems a good time to recall a life well lived.

His father had been postmaster in the west Cornish village of Breage. He’d also been a member of the church choir and a lay reader.

“He was a big influence on me,” says Michael. “He was a very devout man.”

At the age of eight, Michael met his first bishop. It was 1947, and Bishop Joseph Hunkin was visiting the village to dedicate a memorial to those lost in the recent war.

“I was very disappointed,” Michael laughs. “He was only about five foot tall, and he didn’t have the mitre. He was very low church.”

Nevertheless, this encounter came at an important moment in the story of Michael’s spiritual awakening.

“I distinctly remember it,” he says. “It was the first time I was a fully-fledged choirboy in my cassock and surplice.”

But it wasn’t until some years later that he came fully to acknowledge the seriousness of his own vocation.

A mission in life

He’d just finished his school exams and his mother had arranged for him to become an articled clerk with a firm of chartered accountants in Helston.

“I said – No way, I’m going into the Church. She said – There’s no money in that!”

His father was of course very pleased by his decision, and his mother was, as he says, eventually reconciled to it.

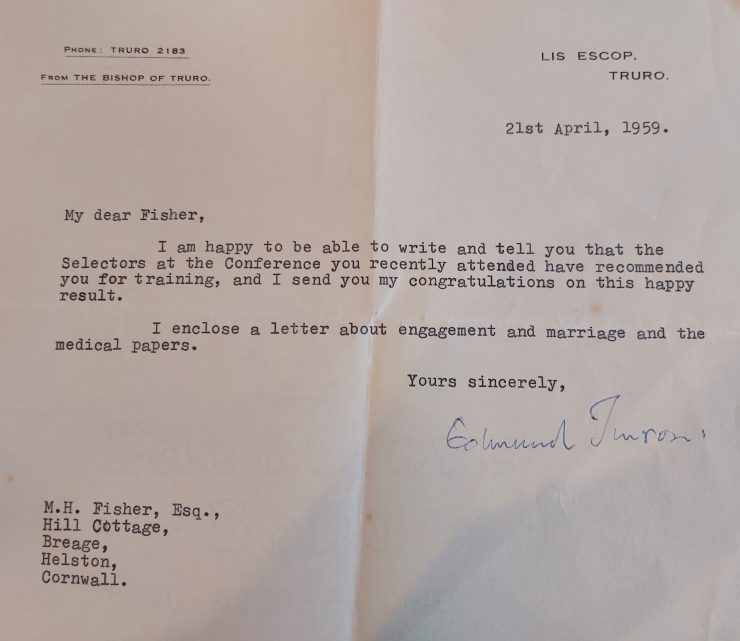

He was 19 years old when he was accepted for training into the ministry. He still has the bishop’s rather brief letter. It was a small piece of paper that would change his life.

He went on to study English Literature at Exeter University, but on his arrival, when he told his English professor that he planned to become a priest, that esteemed man of learning suggested he should transfer forthwith to the theology course.

“My academic career at Exeter was undistinguished,” he recalls. “I scraped a degree. I read widely but not wisely.”

His best man said at his wedding reception that Michael had read every book in the university library, apart from the ones he was supposed to read for his course.

He then progressed to St Stephen’s House at Oxford to complete his training. In his final ordination exams, he’d had to write a long paper on sexual ethics. It was not, he admits, a subject in which he had developed a great deal of expertise.

At that time he also worked two days each week at a local psychiatric hospital.

“In some ways that was more valuable than what I learned at the college,” he says. “If I hadn’t gone into the ministry, I think I’d have wanted to work as psychiatric nurse.”

Raised by Wolves

It was now the 1960s. Having missed out on obligatory national service by only about six weeks, Michael was ordained at Lichfield Cathedral and commenced a curacy at Wolverhampton Parish Church.

“I didn’t even know where Wolverhampton was,” he admits.

There in the Midlands he found what he calls a very large and very varied ministry.

“We had two church schools – I was chaplain for one. We had a group for people with hearing difficulties – they called it the ‘deaf-and-dumb club’ in those days. And we had a home for unmarried mothers – which I was deemed too young to go into.”

After four years in Wolverhampton, he was invited to take on a curacy back home in Cornwall.

“We would like you to come to Newquay,” the Bishop had written. “It is not typical Cornwall.”

He recalls one visit to a recently bereaved family in his new parish to discuss the arrangements for their father’s funeral. He found the four sons sitting silently in a darkened room. He asked what the deceased gentleman had been like.

“He were a rum ’un,” one of the sons had said.

“He had many individual characteristics,” the young clergyman had written in his notes.

Michael had married in September 1964, while still in Wolverhampton, and his new wife Rosemary was keen to see Cornwall. By then, they had also been blessed with their first child, the first of two daughters.

Michael served as a curate in Newquay for three years. He recalls that the rather unorthodox vicar in charge always called him ‘boy’. This was not the limit of his eccentricity.

“He said it didn’t take any longer to put things away tidily in church than to put them away in a messy way. Unfortunately, he didn’t apply this principle to his own home. But he was a very saintly man.”

The young vic

That priest’s successor, Michael notes, was also a very good man. He recommended Michael to replace him as vicar of Newlyn, near Penzance. At the age of 30, he was the youngest incumbent in the diocese when he arrived there.

He remembers the first time he walked into his new church. “A couple of the older parishioners were talking. Is that the new vicar?, asked one. No can’t be, said his friend, it’s only a boy.”

In Newlyn he also served as chaplain to the lighthouse service.

“I’d get hoisted up onto the lighthouse or the lightship to visit them. I didn’t really do anything for them other than listen. One old fellow told me I wouldn’t find a lot of churchgoers there.”

In 1975 he’d relocated to Launceston as priest-in-charge, and after eight years there he and his family had moved on to Carbis Bay. He was appointed an honorary canon at Truro Cathedral in 1985.

They had been a decade in Carbis Bay when Rosemary had fallen ill.

They’d been living in an unsuitably grand place south of St Ives, with a massive garden and even a tennis court. Rosemary herself had designed a new house for them to live in.

The diocesan architect hadn’t especially liked the design. He’d thought there were too many windows. “The degree of fenestration denotes the hand of Mrs Fisher in this design,” he’d said.

But her illness had worsened. Rosemary hadn’t lived to see their new home blessed.

After her death, the Bishop had suggested that Michael move back to Newquay. The job there had been vacant for a while, the church had burnt down, and rows were raging locally as to how to rebuild it.

It proved to be a fresh start both for Michael and for St Michael’s Church.

A few months after his arrival in Newquay, he met Jan. They had both been recently bereaved. Both had lost beloved spouses to cancer.

He’d answered a notice she’d placed in Saturday Rendezvous, the ‘personals’ column of The Times.

“It was before internet dating,” Jan explains.

She’d received twenty-five replies. “Go for the vicar,” her son-in-law had advised.

Jan recalls that a scandalized parishioner had once asked if it was true that she’d advertised for a husband. She’d confirmed that she certainly had.

They had fallen in love and married quickly. “I couldn’t have a live-in lover, could I?” Michael laughs.

They were married in the church hall in November 1995, because the church itself was still being rebuilt and was encased in scaffolding. It is to this day the only wedding ever to have been conducted at St Michael’s Church Hall.

The rest, as they say, is history. They’ve now been happily married for more than twenty-seven years, and are clearly still very much in love.

Too much in the sun

After four more years at Newquay, Michael and Jan had the opportunity to move to the Costa del Sol, where he had been offered a chaplaincy position. It wasn’t, they now feel, their wisest move. Their stay on the Spanish coast hadn’t proven the sojourn in paradise it had at first appeared to be.

On their return to the UK in June 2000, Michael took early retirement. “And I’ve been working ever since,” he says.

Since then, he’s worked in Dartmoor and Ireland, and served for ten years as a relief chaplain on the Isles of Scilly. But he’s kept coming back to his native Cornwall again and again. He currently assists the Rector of Padstow in working to support the five churches there.

The energetic octogenarian now looks back at his sixty years of service as having been what he calls “an immense privilege”.

“People let you into their most joyful moments and their saddest moments,” he says.

He recalls what an old friend had said when asked why she had been ordained.

“She said she could only describe it as having been a godly niggle. That’s exactly how it was for me. It was always at the back of my head that it was something I ought to do.

“In some ways in wasn’t something I chose. But, if I had my time all over, I’d do it again.”

A special service to celebrate Michael’s life of ministry will be held on Sunday 11th June at 3pm in St Saviour’s Church, Trevone.