Survive and thrive

“We may need a moment of silence as we learn, but in the end silence is not an option. I hope and pray that we all go from here changed… never to be complicit with silence.”

With those words, on Monday, Father Simon Robinson, Dean of Truro, opened an exhibition of the work of the survivors of church-related abuse.

“It is absolutely right and proper that the church acknowledges abuse and the devastating impact that it has on individuals and families,” he said. “This feels like a moment of real truth.”

WHEN I WAS A CHILD

Sarah Troughton grew up in the northeast of England. David Creese grew up in rural Canada. Both are survivors of church-based abuse.

Sarah was raised in an environment of domestic abuse. As a teenager, she looked to her church for a safe space.

Her youth leader, knowing her background, invited her into his home, and exploited her vulnerability to abuse her sexually, emotionally and spiritually.

She had tried to report it but hadn’t been taken seriously by her church.

“Safeguarding then wasn’t what it is now,” she explains.

It was only when as an adult she brought the matter to the attention of the safeguarding lead at the Diocese of Newcastle-upon-Tyne that she discovered, years later, that her church was now willing to listen to her.

“I’d never felt valued by the church,” she says. But things changed when she and her husband had joined St Aidan’s in Newcastle. “We’re both very accepted there. It was the first church I’d walked into where I felt valued.”

David Creese had a very similar experience. At the age of eight, he had joined his local church choir. Three years later, the choirmaster had started to abuse him.

“It was horrendous, humiliating and above all silencing,” David told an audience at Truro Cathedral on Monday.

Feeling afraid and ashamed, and unable to speak to his family, David confided in a friend. His friend’s father was a retired police officer. A criminal investigation was initiated, and his abuser was sent to prison.

During the investigation, it emerged that similar allegations had been reported when the choirmaster had been at another parish. The church had hushed it up and quietly moved him on.

“I was only abused because of a previous failure of safeguarding,” David says.

His own parish priest had tried to persuade his parents to drop the allegations. Their local church no longer seemed a safe or welcoming space, and his family had moved to another place of worship.

David was also subject to abuse at that new church.

“I felt as if I’d brought it upon myself, that there was some kind of deficit in me that abusers could identify,” David says. “That sense of shame has been a very damaging part of my history.”

In later years, David came to help friends who had suffered similar experiences. These interactions caused his own memories of abuse to resurface in painful and debilitating ways. As result, he had been unable to work for more than two years, after being diagnosed with PTSD.

“The effects on your body and mind are unbearable,” he says.

The involuntary incursions of those childhood memories into his adult consciousness set off what he describes as a vicious triangle of shame, anger and fear.

“The fact that I was scared as an adult, scared in the way that children are scared, made me angry – livid – and that anger also scared me. And beneath all this was the shame.”

When later he discovered that his original abuser was now working at a church in the United States, he decided to report this anonymously and so approached the diocesan safeguarding team in his adopted hometown of Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Like Sarah Troughton, he suddenly found his story taken seriously by his church for the first time.

By this time, he was no longer a regular churchgoer. “It wasn’t that I didn’t believe in God, but my relationship with God had been so damaged by this experience,” he says.

This then was a major turning point. It was through the diocesan safeguarding team in Newcastle that he was introduced to Sarah. They started working together on a project sponsored by their diocese about ways in which the church might learn from survivors how most appropriately to respond allegations of abuse.

LET THE LITTLE CHILDREN COME TO ME

Together they created a set of principles and a way of making them accessible through art and music. This work is on show at Truro Cathedral until 22nd March. The exhibition is called ‘If I told you, what would you do?’.

Sarah now works for the Ministry of Defence as a psychiatrist specialising in trauma.

“Trauma’s my business,” she laughs. “It’s very much my bread and butter.”

Sarah was able to combine her professional knowledge with her love of art, in collaborating with David to develop and communicate their survivors’ strategy for the Diocese of Newcastle.

“My first dream was to be an artist – before it was to be a doctor,” she told an audience at Truro Cathedral on Monday morning.

She emphasizes that she’s now much more of a thriver than a survivor. “Having my art exhibited on the walls of a cathedral – that’s my dream. I’m flourishing,” she says.

Sarah stresses that she’s grateful for this opportunity. “I feel that my story is now being honoured. I feel this is the culmination of that story, and that something is now being done, and that hopefully it will help other people as well.”

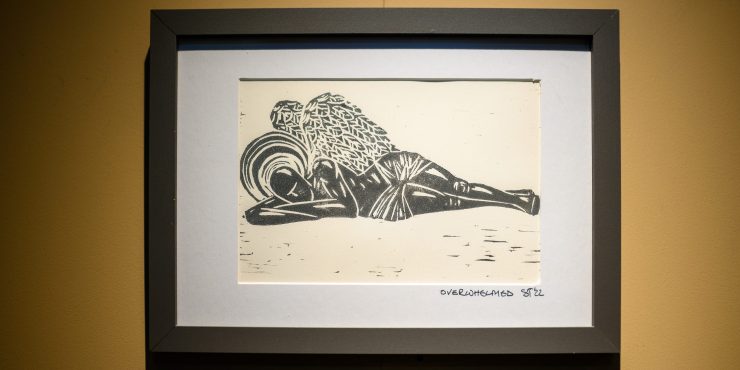

She has created an arresting set of prints which chart the emotional journey of the survivor of abuse, from the point of being overwhelmed by the original experience of that absolute betrayal of trust, through the feelings of fear, shame and despair, to righteous outrage and the demand for justice. She illustrates these stages through the embodied agency of an angel, stark, lucid, vulnerable and furious.

“I wanted people to be able to relate to a survivor’s experience, and also for survivors to relate to it,” she explains. “To understand that, like grief, you go backwards and forwards on it. The whole church has to go through all that emotion – to feel the shame and the outrage, and to go through the processes of getting its trust, dignity and honour back.”

She points out that “the more we talk about these stories, the more we can be safe.”

But she says that “one of the reasons that the church has responded badly is that it’s been hurt itself. The abuser grooms the whole church. The moral injury has happened to the whole church. It’s really important that we heal the whole church. If we can teach people to respond better, we can really help that wound to heal in the church as a whole.”

The church, she says, must therefore become attentive to these stories.

David agrees. “We are injured survivors and we are members of an injured church. We may call it historic abuse, but it’s not historic for survivors. What we need is to hear survivors’ stories.”

Sarah and David had initially developed a set of principles for trauma-informed care, but they’d felt that if they just posted these to a church noticeboard they would end up being ignored.

“We started thinking about ways that would make them accessible, to make them living, to inspire others,” David says.

So, while Sarah chose to use her abilities as a visual artist to illustrate these ideas, David deployed his talents as a musician to communicate them.

CHILDREN OF GOD

David had grown up on a farm. Behind the farm was a piece of woodland. He had gone there during the greatest depths of his childhood despair.

“In amongst the trees, where I was invisible to everyone but me and God, I could hear the songs of the sparrows,” he recalls.

He was reminded of Jesus’s words to his disciples in the Gospel According to St Matthew: “fear not… you are worth more than many sparrows”.

He came to associate the voices of survivors with the songs of those blessed birds of the air.

When he started working with Sarah, he therefore chose to create a piece of music which would combine this evocative birdsong with an early church hymn, one with its origins in the fourth century and often attributed to St Ambrose.

It was a hymn to martyrs. “It was written at a time of vivid living memory of people who had suffered for drawing close to God,” he explains. “That’s how I see survivors of church-based abuse – people who’ve suffered from drawing close to God.”

St Ambrose had written of the perfect love of Christ, a love which, David reminds us, cast out shame.

David imagined the church, through the hymn of St Ambrose, responding to the voices of survivors of abuse, expressed in the songs of the sparrows.

“To reach out and value what it hears, to find an affinity in what it hears, for the voice of the church to sing in harmony with them…”

Performed on Monday at Truro Cathedral by Saint Mary’s singers, this piece of music was at once visceral and ethereal, sensitive and profoundly moving, gentle yet haunting, troubled yet serene. Its beauty reconciled suffering, grief and grace into the understanding of numberless voices released to sing as one.

One visitor said that he didn’t think he’d ever been moved so much in the cathedral as he’d been that Monday morning. Another stressed that she felt it was vital that we get David and Sarah’s messages out to our congregations and our communities.

The Bishop of Truro, the Right Reverend Philip Mounstephen spoke at the opening of the exhibition.

“We’ve been far too quick to speak dismissively and too slow to listen attentively, and, for that and so much more, I apologise,” he said.

“Safeguarding is all of our business. It’s core to our business because it’s God’s business.”

He stressed that we all owe a great debt of gratitude to people like Sarah and David for giving us this opportunity for transformation, healing and growth.

“This is all about us facing up to something very shameful in the life of the church that we’d like to say belongs to our past, but we must admit is also part of our present,” he added. “Only by facing up to this and acknowledging it for the sin and scandal that it is can we hope to address it.”

After 13 years in her role, the Diocese of Truro’s Head of Safeguarding Sarah Acraman will be leaving us at the end of this month. “This feels like a real pinnacle event,” she says. “It shows a growing commitment to stand alongside those who’ve been affected by abuse. I’m proud to be part of this.”

“It’s vital that the church finds spaces to listen to the voices of survivors,” adds Diocesan Secretary Simon Cade. “If a single survivor feels able to speak following this work, it will all have been worth it.”

‘If I told you, what would you do?’ runs at Truro Cathedral until 22nd March. Entry is free and all are welcome. If you have any safeguarding concerns, please do not hesitate to to contact our safeguarding team at: safeguardingconcerns@truro.anglican.org