Keeping Cornwall safe in the Home Guard

Roy in the Home Guard, first row, first on the left

Roy Olver was 16 when war broke out. He was living and working on his family’s farm at Terras, just outside of St Stephens near St Austell, and remembers Mrs Bilkey rushing out of her cottage crying that we were at war.

“I couldn’t understand why she was so upset,” says Roy. “I didn’t really know what war meant.” But to Mrs Bilkey, whose husband had fought in the First World War, it meant a great deal, as Roy came to realise.

Roy has worked on farms all his life. He left school at 13 when his brother had an accident that left him partially blind and the family farm needed his help. “I’ve been very lucky. I love farming and I loved what I did – my best days were walking behind the horses. They did all the work, I just dropped the seeds.”

Farming without mechanics

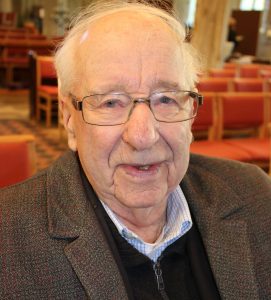

Roy Olver

Roy didn’t just drop seeds. His work was very physical, hard and with long hours. Especially during the war when Double Summertime was imposed. Roy would work on threshing, which was all done by hand ,as there were no combine harvesters then, thatching and on the potato crops. “Double summertime was awful! You’d get up just as early but not be able to do what you needed to the crop as there was still dew on it. So you filled the time with other jobs and then worked in the fields until the light faded after 10 o’clock.”

“Those in the army didn’t get to worry about the clock. I didn’t see that I had anything to complain about.”

But Roy was grateful. “Those in the army didn’t get to worry about the clock. I didn’t see that I had anything to complain about.” Roy was exempted from joining up as he was needed at home. His father was too old to go and, after his accident, his brother wasn’t fit enough to serve or manage the farm, so the very young Roy had to take on the job. The country was in great need of food as overseas supplies had been intercepted and the country had to become self-sufficient.

Health and safety? There was no such thing, laughs Roy

“The government controlled everything and took most of the food we produced. Every farm had to produce a certain acreage of crop. We had to do wheat and potatoes, which involved a lot of carrying very heavy sacks!”

In fact, Roy had to lug around sags of produce weighing 140lbs, 3 times the legal limit today of what’s considered safe today. He laughs at the concept of health and safety, ““There was no such thing! You just got on and did what had to be done.”

The Home Guard was more than Dad’s Army!

What had to be done included joining the Home Guard. Twice a week, after a full day at work, Roy would either be training or on surveillance. One of his jobs was to patrol the railway. “It’s amazing how your eyes adjust even when it’s pitch black – which it was as we didn’t have any lighting at all, not even a torch.”

The Home Guard were much more than Dad’s Army suggests. Answering a call to action in 1940, nearly 1.5million men between 17 and 65 who were ineligible for front line action enrolled to man the defences at home. Starting with barely enough uniforms and armed only with rifles and whatever passed as a weapon, including golf clubs, the Home Guard grew into a force to be reckoned with that prepared the country for invasion. They also became involved in bomb disposal, manning anti-aircraft and costal artillery. Throughout the war, over 1200 Home Guards were killed on duty or died of wounds.

Potential intruder or late-night clergy?

Asked if Roy ever caught anyone, he explains how one night he and his fellow home guards heard rustling out of the darkness and saw a figure come towards them. On high alert, they asked the figure to identify themselves, “It was old Canon Gilbert from the parish – he just wanted to see how we were getting on!”

After his shift, which finished at 5 in the morning, Roy would go on to his day’s work. “It’s just what we did – by the time I got home it was too late to go to bed so I would just work and go to bed in the evening.”

A POW, Land Girl and thousands of GIs

Roy remembers having help on the farm from a POW. “He was a lovely chap, a young cabinet-maker from Austria, I think. He didn’t want to go to war. His father’s business was forced to close and he was sent off to the army, barely trained then captured within months.” The prison camp was at White Cross and the prisoners were dropped off every day. Roy and his family made sure to show him some Cornish hospitality, “He ate with us at midday and he was so grateful. It was sad really. He was a good chap, he helped me put up a shed when I didn’t have a clue what to do – he was very talented. I don’t know what happened to him, one day he left and we didn’t hear anything more.”

The farm also had help from a land girl, “She was very good! We didn’t have any electric so she had to milk the cows by hand, in fact there wasn’t much she couldn’t do!”

Roy also remembers the GIs. “Thousands of them! They were camped out in all the fields, along the lanes.” Roy saw them trying to take some hay and asked them what they were doing. They said they needed it for their beds and so he delivered a truck load for them. The GIs filled Cornwall in the months leading up to D Day. Like Roy says, one day they filled the county, hiding in encampments along the creeks and in the fields, and the next day they were all gone. It was June 6th and every single serviceman left our shores to face the horrors of the Normandy beaches for Operation Overlord, or D Day, the event that turned the tide of WWII.

A farmer for life

After the war Roy married Dorothy and took on his own farm, handing it over to his son when Roy was 65. “I kept my hand in though until I was 80. Must have walked thousands of miles with those horses in my day, which is my knees are not so good now but I loved it. I found sitting on a tractor melancholy.”

There is nothing melancholy about Roy today. His eyes shine as he shares his stories into how life was for him as a serving member of the Home Guard and working the very long hours as a farmer, doing his bit to make sure the country had enough food.